Art Restoration History Articles

Art restoration history articles

saved and preserved.

From our beginnings in 1850 until today we have restored 1000’s of artworks.

Established in 1850, Oliver Brothers is the oldest fine art restoration and conservation company in the nation. The following are art restoration history articles we found in our archives. The articles were published in many newspapers and magazines from 1961 to 1986.

BOSTON SUNDAY ADVERTISER

Turning Back The Centuries

JUNE 18, 1972

By SALLY CARSTAIRS

AMID THE SWEET painty smells of a studio basement in the Back Bay, ancient art and modern science are making a rendezvous.

The studio belongs to Oliver Bros., Inc., art conservators. No Olivers remain in the firm, but the two proprietors, Carroll Wales and Constantine Tsaousis, carry on a century-old tradition of preserving paintings.

Wales is a friendly New Hampshirite who aspired to be a professional artist during his training at Harvard’s Fogg Museum. He met his partner in Istanbul, where Wales went to help restore Byzantine mosaics.

Tsaousis was a former tailor who had been asked by the director of Istanbul’s Byzantine Institute of America to learn conservation. The men are among the few conservators in the United States who specialize in restoring mosaics and paintings done on wood.

Their delicate work requires thorough knowledge of painting techniques and art history. In addition, modern chemistry has introduced them to improved methods of restoration.

“Paintings take months, sometimes more than a year, to restore,” Wales comments. “We spend so much time in front of each canvas that anything that saves time and effort is welcomed.”

Modern acrylic paints, which do not darken with age (as oil paints do) and which can be removed without destroying oils below or around them, have eased their task.

Another favored innovation is PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone), a GAF Corp. chemical that has many uses, ranging from consumer cosmetics to decontamination of astronauts returning from the moon.

The conservators use PVP plus long-fiber, wet-strength paper (the same stuff that tea bags are made of) to protect the paint on a canvas being restored.

“Canvases tend to stretch and shrink, stiffen and loosen as they are affected by temperature, humidity and time,” explains Wales. “With all this moving around, the paint on the canvas cracks, then begins to flake off.

“To prevent this from occurring any further, we attach an aluminum and muslin lining to the back of the canvas with wax. The wax takes the place of glue, which is an animal product and therefore tends to dry up and lose its effectiveness with age.

“The stiff backing is applied with a heavy press. If we don’t protect the painting it will come off on the press, so we make a sturdy, opaque shield by applying the special paper with PVP. The facing adheres until time for retouching the painting, when we remove the paper with water.

“Most conservators use wheat paste on the facing, but that is much more trouble — it has to be mixed with an egg beater and then strained.”

Wales and Tsaousis heard about the chemical from a fellow conservator, Morton Bradley of Arlington. In like manner, they broadcast their own “finds” because, Wales says, “All conservators have the same goal — preserving old and valuable art. There is plenty of work for good restorers, and word should be spread on the right materials.”

The Boston Sunday Globe

Gettysburg Battle Canvas Being Restored

October 14, 1962

By EDGAR DRISCOLL

“Lest we forget” might be its sub-title, now that the Civil War is being refought in headlines ‘round the world.

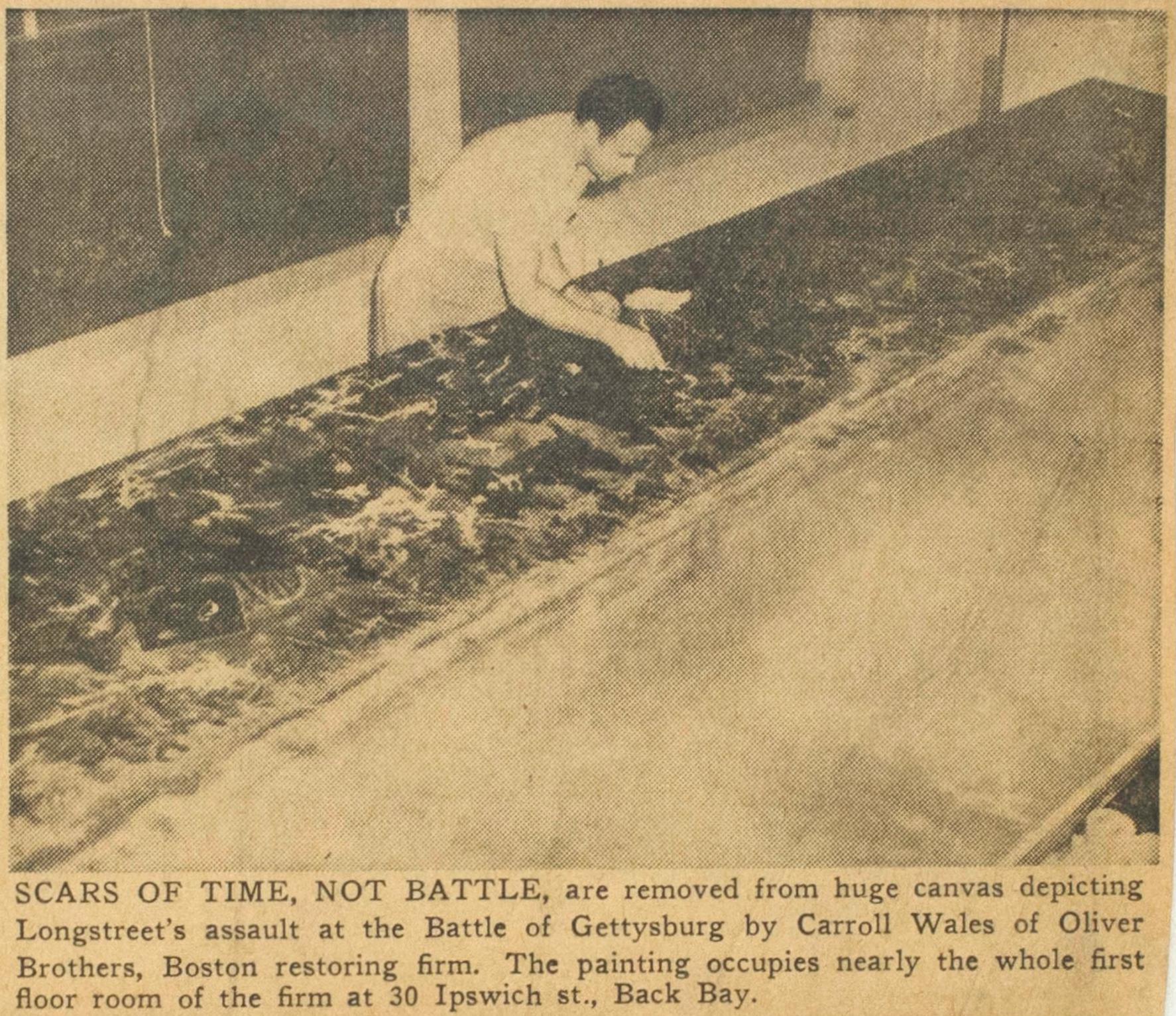

Taking up most of the work area in an Ipswich st. Back Bay, studio these days is a huge recently uncovered canvas depicting the decisive repulse of Longstreet’s Confederate Assault at the Battle of Gettysburg.

The men in blue and the men in grey lock horns in mortal combat. Soldiers by the hundreds lie dead and wounded. Horses, writhe in agony. The smoke of battle rises like something from Dante’s inferno over the once placid green meadows and farmlands of Pennsylvania.

The 94-year-old canvas, some 20 feet long and seven-and-a-half high, is being restored after years of neglect — by Oliver Bros., well known Boston restoring firm in their Fenway Studio offices, 30 Ipswich st.

It was painted by the 19th century American artist, James Walker, after exhaustive research on the subject by a Civil War historian, John Badger Batchelder. He arrived at the battlefield while the dead still were strewn about.

So moved was he by the sight, that he spent the next 84 days (the assault took place July 3, 1863) carefully sketching the 25-square miles which made up the battlefield, including the fields, forests, houses, barns, hills and valleys.

SCARS OF TIME, NOT BATTLE, are removed from huge canvas

depicting Longstreet’s assault at the Battle of Gettysburg by

Carroll Wales of Oliver Brothers, Boston restoring firm.

The painting occupies nearly the whole first floor room

of the firm at 30 Ipswich st., Back Bay.

Next he spent two months in hospitals interviewing Confederate prisoners and, as they became convalescent going over the field with many of their officers. The latter located their positions and explained the movements of their commands during the battle.

Then Batchelder visited the Army of the Potomac, __ suiting with its commander-in-chief, corps, division and brigade commanders. They went over the battlefield drawing with him, locating upon it the position of their respective commands.

From the information thus obtained, the historian was able to trace the movements of every regiment and battery involved from the commencement to the close of the engagement.

After further checking with more than 1000 officers, including 46 generals, Batchelder commissioned Walker to paint the huge canvas. It is populated with literally thousands of troops stretching as far as the eye can see. All are identifiable through regimental flags, caps and insignia, such as Massachusetts volunteers.

He also wrote a book on the subject

The painting is owned by Howard S. Berger of Brookline. He plans to sell it through the Vose Galleries of Boston. When painted in 1868, it was closely examined by Lt Gen James Longstreet himself. He spent several hours in Walker’s studio pouring over the panoramic scene.

Then, with a sad smile, he turned to Bachelder and said:

“Colonel, there’s where I came to grief.”

“Yes,” Bachelder, a colonel with the Union Army, replied. “I have called your assault the ‘tidal wave’ and the copse of trees in the center of the picture, the ‘high water mark’ of the rebellion.”

“You said rightfully,” Longstreet declared.

“We were successful until then. From that point we retreated and continued to recede, and never again made successful headway.”

The huge, fascinating canvas, which had been taken from its stretcher and rolled up many years ago, is being painstakingly restored by Oliver Bros. It was acquired, in its present tattered state, by Berger.

The work, in progress for several months, is expected to be completed in a month or so, at which time the Vose Galleries plan to give it a public airing.

To do so, the restoring studio will have to take out a huge window to remove the canvas, and the Vose Galleries perform an air lift to get it into their Boylston st., galleries.

Walker, (1819-1889) was born in England but reared in New York City, where he maintained a studio most of his adult life. He served as an interpreter in the Mexican War and later was commissioned to record the Battle of Chapultepec for the U.S. Capitol.

During his lifetime he painted many historical canvases, mostly of the Civil War.

After rendering the large canvas of Gettysburg, Walker did a smaller, though almost identical version of it, which he planned to send to England to be engraved. It is now owned by the New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord N.H., and was included in the big Civil War exhibition of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts last February.

*note

“The Battle of Gettysburg: Repulse of Longstreet’s Assault July 3, 1863”, by James Walker (1819- 1889) is located at the Johnson Collection, Spartanburg, SC LINK

Wisconsin State Journal

Wisconsin State Journal, June 16, 1970

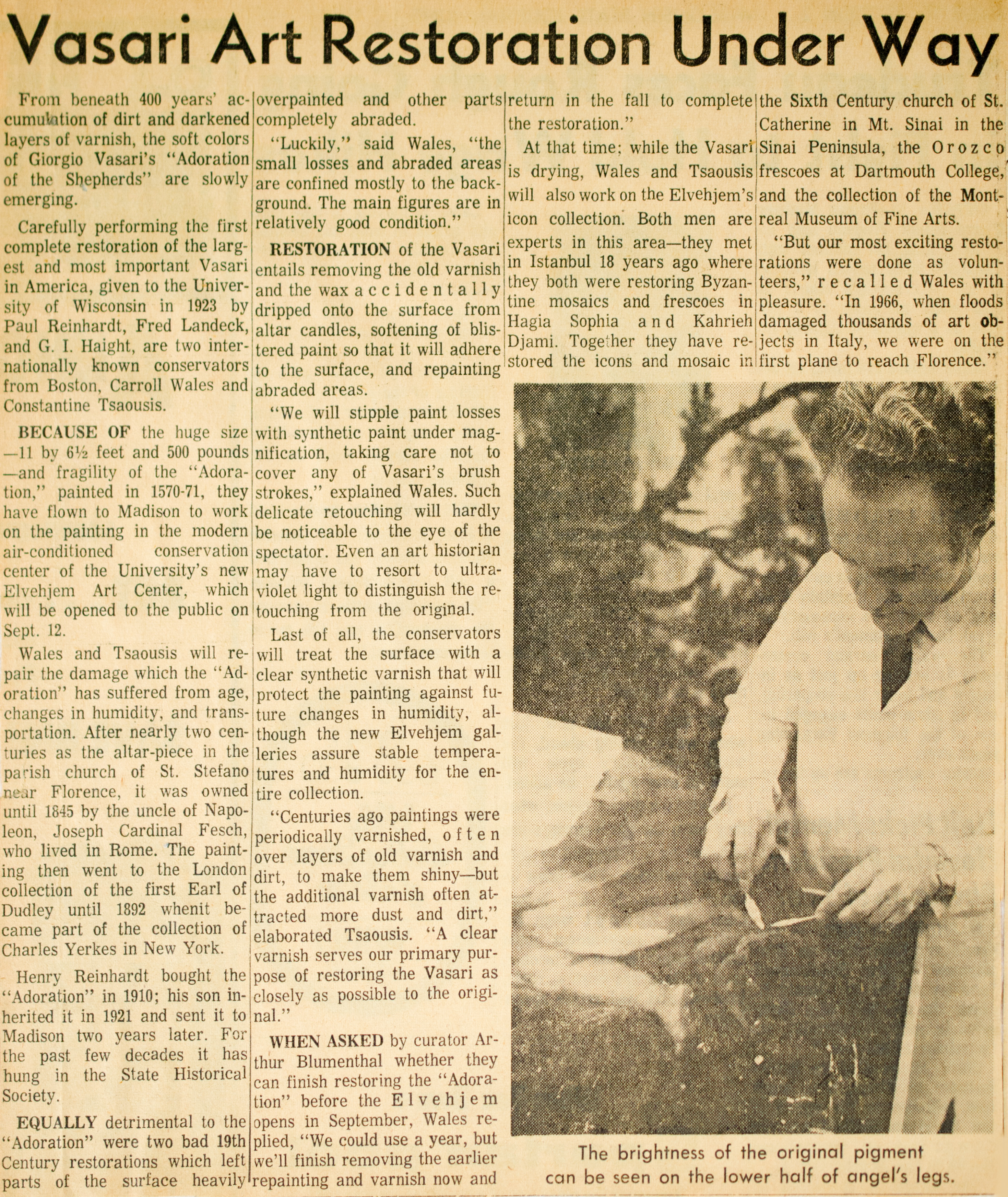

The brightness of the original pigment

can be seen on the lower half of angel’s legs.

Vasari Art Restoration Under Way

June 16, 1970

From beneath 400 years’ accumulation of dirt and darkened layers of varnish, the soft colors of Giorgio Vasari’s “Adoration of the Shepherds” are slowly emerging.

Carefully performing the first complete restoration of the largest and most important Vasari in America, given to the University of Wisconsin in 1923 by Paul Reinhardt, Fred Landeck, and G.I. Haight, are two internationally known conservators from Boston, Carroll Wales and Constantine Tsaousis.

BECAUSE OF the huge size-11 by 6 ½ feet and 500 pounds-and fragility of the “Adoration,” painted in 1570-71, they have flown to Madison to work on the painting in the modern air-conditioned conservation center of the University’s new Elvehjem Art Center, which will be opened to the public on Sept. 12.

Wales and Tsaousis will repair the damage which the “Adoration” has suffered from age, changes in humidity, and transportation. After nearly two centuries as the altar-piece in the parish church of St. Stefano near Florence, it was owned until 1845 by the uncle of Napoleon, Joseph Cardinal Fesch, who lived in Rome. The painting then went to London collection of the first Earl of Dudley until 1892 when it became part of the collection of Charles Yerkes in New York.

Constantine Tsaousis , left and Carroll Wales remove varnish

from “Adoration of the Shepherds.” White spots are abraded areas.

Henry Reinhardt bought the “Adoration” in 1910; his son inherited it in 1921 and sent it to Madison two years later. For the past few decades it has hung in the State Historical Society.

EQUALLY detrimental to the “Adoration” were two bad 19th Century restorations which left parts of the surface heavily overpainted and other parts completely abraded.

“Luckily,” said Wales, “the small losses and abraded areas are confined mostly to the background. The main figures are in relatively good condition.”

RESTORATION of the Vasari entails removing the old varnish and the wax accidentally dripped onto the surface from altar candles, softening of blistered paint so that it will adhere to the surface, and repainting abraded areas.

“We will stipple paint losses with synthetic paint under magnification, taking care not to cover any of Vasari’s brush strokes,” explained Wales. Such delicate retouching will hardly be noticeable to the eye of the spectator. Even an art historian may have to resort to ultraviolet light to distinguish the retouching from the original.

Last of all, the conservators will treat the surface with a clear synthetic varnish that will protect the painting against future changes in humidity, although the new Elvehjem galleries assure stable temperatures and humidity for the entire collection

“Centuries ago paintings were periodically varnished, often over layers of old varnish and dirt, to make them shiny-but the additional varnish often attracted more dust and dirt,” elaborates Tsaousis. “A clear varnish serves our primary purpose of restoring the Vasari as closely as possible to the original.”

WHEN ASKED by curator Arthur Blumenthal whether they can finish restoring the “Adoration” before the Elvehjem opens in September, Wales replied, “We could use a year, but we’ll finish removing the earlier repainting and varnish now and return in the fall to complete the restoration.”

At that time; while the Vasari is drying, Wales and Tsaousis will also work on the Elvehjem’s icon collection. Both men are experts in this area-they met in Istanbul 18 years ago where they both were restoring Byzantine mosaics and frescoes in the Hagia Sophia and Kahrieh Djami. Together they have restored the icons and mosaic in the Sixth Century church of St. Catherine in Mt. Sinai in the Sinai Peninsula, the Orozco frescoes at Dartmouth College, and the collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

“But our most exciting restorations were done as volunteers,” recalled Wales with pleasure. “In 1966, when floods damaged thousands of art objects in Italy, we were on the first plane to reach Florence.”

*note

Giorgio Vasari’s (Italian, 1511 – 1574) “Adoration of the Shepherds” painting is still located at the Chazen Museum of Art (formally Elvehjem Arts Center), University of Wisconsin, Madison. LINK

More art restoration history articles to come….

Back to our Fine Art Restoration, Repair & Conservation Services page | or directions to our Studio LINK