Portrait of Young Boy, by Enoch Seeman the Younger,and its companion

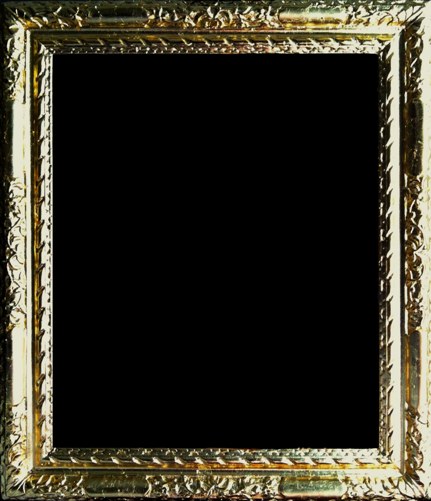

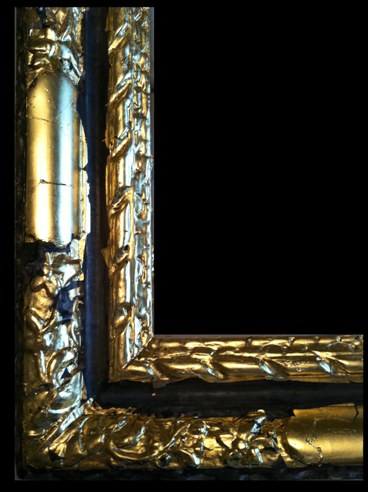

Peter Lely-style picture frame; painting and frame restoration example

Painting Restoration

Many works of art have lifespans that last for centuries. For instance, a painting restored by us recently, Portrait of Young Boy, by Enoch Seeman the Younger, was painted in the early 18th century. The eyes of its subject have silently watched the passage of nearly 250 years (its frame even longer)! Yet, with long age comes eventual deterioration – this is true for artwork just as it is for most other objects. For paintings, everything from environmental changes to the specific materials used by the artist can contribute to the degradation of a piece over time. Fortunately, periodic restoration of artwork can help to significantly reverse the ravages of time. This portrait is a perfect example of the necessity, and care that goes into restoring such an old painting.

Enoch Seeman The Younger (1694-1744) was a Polish painter of moderate notoriety. Born in the city of Danzig, Poland around 1694, he was brought to London by his father in 1704. It was there, i

n 1708 (at the age of 14) that the Younger’s formal career began with a group portrait of the Bisset family, done in the style of Godfrey Kneller – a leading English portrait painter of the period. Over the next several decades, Seeman received commissions to paint at the English court, and eventually, a royal patronage from 1730-1738. Several of his most well known paintings were executed during this eight-year span, including portraits of both George I and George II (the latter is part of the royal collection at Windsor Castle) and a rendering of Sir James Dashwood. While well respected, Seeman the Younger’s style is considered to be conservative in comparison to some of his contemporaries (Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and others).

As an artistic style, portraiture grew considerably in early modern England (16th-18th centuries). While the Protestant Reformation contributed to a decline in commissioned religious paintings, a relatively stable English government, combined with a powerful aristocracy, made portrait artistry a financially (and socially) viable profession. The market for these portraits flourished in the 18th century, and as a result, artists like Enoch Seeman the Younger congregated to wealthy areas like London. Here, respected artists were regularly commissioned for portrait paintings by a variety of individuals – from the middle classes all the way to Royalty.

The collection of portraits also became extremely popular during this period. As the style gained notoriety, members of the English upper classes began to amass large private collections. Consequently, the works of many prominent artists were spread far and wide throughout the world. At least one Enoch Seeman portrait traveled as far as Virginia during the 18th century.

Some questions currently remain unanswered about this particular Seeman painting, Portrait of a Young Man. Primarily, the name of the sitter, and by whom it was commissioned are unknown. We can, however, determine a few things. For instance, based on the subject’s attire and setting, he was most likely the member of a wealthy family. Also, the painting was almost certainly executed after Enoch Seeman arrived in London, putting its date somewhere between 1708 and 1744.

Artwork of this age almost always has an additional history as well – something fine art conservators can tell through careful examination of what a painting has gone through over the course of its lifetime. This was the case when the Portrait of a Young Man arrived at Oliver Brothers recently. The most obvious signs of age were a film of dirt and grime, some staining throughout the artwork, a dent below the subject’s hand, and areas of paint loss. There was also a significant amount of cupped craquelure throughout the artwork. This is a common problem, which can be caused by several different factors, but is most typically due to the different rates of expansion and contraction of the paint film and ground (the base layer) upon which the paint film is adhered to.

Painting and frame after restoration

Painting before restoration

Frame detail- before restoration

Closer inspection revealed other clues to its past. Most notably, the painting had undergone at least two or more restoration treatments. For example, we discovered an old glue lining that was over 100 years old. The lining had dried out and needed to be removed before the portrait could be repaired. There was, however, a relatively light amount of dirt and grime, thereby indicating that the painting had been cleaned long after the old glue lining was attached to the artwork. Cleaning tests also revealed multiple layers of old inpainting; further evidence of prior restoration treatments.

One thing was certain: the portrait needed new restoration to ensure its continued longevity. The first step included cleaning the artwork and removing the old varnish, as well as the layers of old inpainting. Next, the old lining had to be taken off. This proved to be somewhat of a hurdle, as the old glue adhesive was dried out and needed to be softened with a combination of solvents, enzymes, and hot water to ensure it could be totally removed. Once completed, the original fabric support of the artwork was “relaxed” with a proprietary Oliver Brothers process. After that, the painting was relined with Belgian Linen and a sheet of Mylar to help hold down the areas of craquelure, and then stretched onto the original stretcher bars. Finally, a protective coat of varnish was applied to isolate the original paint film and judicious inpainting was performed in the areas of paint loss. The appearances of certain areas of the painting, such as the grapes in the background, were greatly improved by this process. Once the inpainting was completed, the painting was framed with its newly restored Peter Lely picture frame.

In the end, Enoch Seeman the Younger’s Portrait of a Young Man, already several hundred years old, had a new lease on life. And while no restoration is permanent, the artwork and picture frame will be in very good condition for many years to come.

Frame Restoration

A picture frame was severely distressed . The gilding was all but washed away, traces of gray bole on what was left of the checkered and cracked white gesso surface. Looking past the lost layers of gilding we found a lovely example of a hand carved Lely frame. Dating to around 1660, there was no doubt that this frame had good bones, even though its surface didn’t currently show it.

Peter Lely (1618-1680) was a Dutch painter who moved to England (where he spent most of his career) around 1641. Appointed principle painter of the British court in 1661, Lely painted many of the portraits of English nobility and wealthy individuals for the next 20 years. Being a very popular portraitist, Lely and his workshop became prolific in their production of portraits.

Unfortunately, not much is known about who designed or made his frames. We do know he favored a few patterns, however, which are now recognized as “Lely” frames. They are based on the French Louis XIII frame styles, popular during the second half of the 17th century. These frames were gilded and carved in shallow relief, using variety of patterns for rich effect. There were flowers, vines and acanthus leaves, as well as areas where the gold and gesso were punched to create a hammered metal look. There were mirrored “reposes,” or, smooth, flat, and convex areas where the gold was shined to a high burnish, emulating a mirror. The burnished gold serves to highlight the work of art and to reflect light into the painting. Rooms in the 17th Century relied on natural light during the day and candles and or a fireplace at night. Therefore, any additional light on the artworks was most welcome.

When we restore art objects, we must consider many things: how they are appreciated in our lives today, how they were appreciated or consumed in the past, and the artist’s original intention. Sometimes these are at great odds with one another and we make compromises. Sometimes they are one and the same.

In the case of this Lely frame, our goal was to restore it to a condition similar to its original state: gilded, with selected areas burnished to a high sheen. The painting, a Portrait of a Young Man by Enoch Seeman the Younger, was being cleaned and restored at the same time. The objective was for the two companions to look brilliant together, like they each did in England a long time ago. Though this could very well be the original frame for the painting, as they are from the same time period, it just as likely may have been chosen at some later date – court paintings were all standard sizes, and the frames interchangeable.

Nevertheless, the surface restoration process for this frame was done using traditional gilding methods. While the frame had been gilded at least twice before, the gilt surface that remained was in no way original, and did not require preservation. The first step, then, was to remove all the dirt, dust, and the rough uneven surface. A thin layer of the upper “new” layers of gilding was sanded off to reveal the original punched pattern on the frame which had been obscured. It followed the pattern of the classic Lely frame – round punch-work near the florals and zigzag lines – so we knew what to strive for in the end result.

Lely frame before restoration

New Gilding before toning

After carefully performing the application of the bole, the gilding and the burnishing,, various tools and a hammer are used to carefully punch designs into the surface, recreating the “Lely” pattern.

The new gold that was applied was so bright that it was distracting and overwhelmed the painting. Using a variety of toners and pigments, we calmed down the brashness of the pure gold and gave the frame the appearance of an antique surface in good condition. Adding more antique tone to the “low” areas, and less to the high shiny areas, nicely highlights the carving. The subtle cracks in the finish are a result of the previous cracks, which were in the gesso below. They add to the authentic look of our new surface.

Next, the remaining gesso was sealed with glue (traditional gesso was made from chalk whiting and rabbit skin glue, and was applied in as many as 10 layers until the thickness was appropriate). Long hours were spent meticulously sanding all the flowers, and convex and concave surfaces. The gesso must be sanded for two reasons: to define the carving below and to make a very smooth surface for the application of the bole and the water gilding.

Old re-gilding layers needed to be sanded down to the original layer before the new gilding process could begin

Gilding being put on over black bole

After carefully performing the application of the bole, the gilding and the burnishing,, various tools and a hammer are used to carefully punch designs into the surface, recreating the “Lely” pattern.

The new gold that was applied was so bright that it was distracting and overwhelmed the painting. Using a variety of toners and pigments, we calmed down the brashness of the pure gold and gave the frame the appearance of an antique surface in good condition. Adding more antique tone to the “low” areas, and less to the high shiny areas, nicely highlights the carving. The subtle cracks in the finish are a result of the previous cracks, which were in the gesso below. They add to the authentic look of our new surface.

Finally, the restored painting and resurfaced frame were reunited, looking glorious and very dressed up for their future together!

Frame, before and after restoration

Fully restored Peter Lely picture frame

Back to our Fine Art Restoration, Repair and Conservation Services page

Contact Oliver Brothers or call us to schedule an appointment at 617-536-2323

"*" indicates required fields