Carroll Wales, Part II: Fragments of Samatya

Byzantine Institute / Preservation ARTICLE LINK

Written by Jessica Cebra, ICFA Departmental Assistant

The story of conservator Carroll Wales, and concomitantly, of his conservation sidekick Constantine Tsaousis, continues as more is revealed in the context of the Byzantine Institute’s smaller side projects, by way of a visually rich collection of color slides donated by Wales in the 1990s. In ICFA, our attention is often directed toward major Byzantine monuments in Istanbul such as Hagia Sophia and Kariye Camii where the Byzantine Institute, and later Dumbarton Oaks, worked to restore and conserve the buildings and their interior decorations of frescoes and mosaics, mostly in the 1930s through the 1960s. During these decades, additional smaller-scale projects took place at various sites in Istanbul where Byzantine Institute staff lent their expertise and skills, or co-sponsored the fieldwork with other institutions. While ICFA holds both textual and visual fieldwork documentation for many of these projects, Wales’s personal photography, along with an oral history interview with him conducted by the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, colors the larger picture of Byzantine art conservation from a conservator’s point of view.

Wales and Tsaousis met while restoring the frescoes at Kariye Camii in 1952. Wales grew up in New England and had recently finished his graduate education in fine arts conservation at Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum, while Tsaousis descended from northern Greece, but was born and grew up in Istanbul and worked as a craftsman and tailor. Wales spoke English and some French; Tsaousis spoke Greek and some French. So, naturally, Wales and Tsaousis communicated best in French, at least in the beginning of their friendship. Over the years, they absorbed one another’s knowledge of Byzantine mosaic and fresco conservation. While both had to learn on the job, it helped that Wales had formal conservation training, and Tsaousis already possessed a passion for Byzantine art and a skill set inherited from his architectural engineer father. Wales believed Tsaousis was one of the best. Indeed, the family name Tsaousis derives from the Turkish word usta, meaning “master craftsman.” As part of the Byzantine Institute staff, Wales and Tsaousis worked not only at Kariye Camii, a project that took nine years to complete. They also worked intermittently at various sites where Byzantine frescoes remained and were in danger of further damage and deterioration. These included frescoes at the Church of Saint Euphemia, at a site near the Church of Saint Irene, and at a site simply known as Samatya, which was endangered by imminent demolition.

Referred to both as “Samatya” and “Etyemez” in ICFA’s records, the fresco conservation at this site is the central topic of this post, but as you read on the issue of nomenclature in archives, particularly when dealing with multicultural materials, may become well apparent. Or perhaps this post is my attempt to articulate how it took a trip to Turkey to fully appreciate the relevance of a small conservation project that was initiated on a street corner in the Samatya neighborhood of Istanbul in 1957, especially in light of the Wales materials I have reviewed in the past few months.

Last summer, I traveled with a group of architecture students to survey the remains of late Roman and early Byzantine architecture in a fairly secluded area of the Antalya province on the southern coast of Turkey. In addition to the fieldwork, we took bus trips to other archaeological sites in the region in order to study and compare examples of architecture and city planning from the period of late antiquity. The trip ended in Istanbul, where we were let loose to explore on our own. I had also been to Istanbul the previous summer, so I had already made my necessary visits to Hagia Sophia and Kariye Camii. This time I had other plans, which involved a bus ride to the Theodosian city wall and a long 7 km walk from the wall at Yedikule (Seven Towers) through the neighboring area called Samatya, and all the way back to my hotel in Sultanahmet. At the time, I wasn’t aware the neighborhood I was walking through was called Samatya. All I knew was there were no tourists here, snacks and yogurt drink were very inexpensive, and I was on a mission.

I later learned the Turkish name Samatya derives from the Greek word psamathion meaning “sandy,” as the area was literally very sandy according to Raymond Janin’s topographic account of Byzantine Constantinople. Samatya encompasses the southern area between the former Constantinian city wall and the Theodosian city wall. In early Byzantium, Samatya (or Psamathia) was mostly inhabited by aristocrats, but gradually the mansions were replaced by monasteries. The most notable being the Stoudios Monastery, also known as St. John Stoudios, as it was dedicated to St. John the Baptist. My primary goal on that hot summer day was to find St. John Stoudios, the oldest standing basilica in Istanbul. It was built in the 5th century and housed a monastery which, at its height, was the most important center of intellectual activities like manuscript illumination, calligraphy, and poetry, and served as the model for other monasteries such as those on Mt. Athos. St. John Stoudios led the Byzantine artistic and cultural renaissance of the 9th century.

There had been recent news that the city of Istanbul was planning to renovate the structure and build a new roof, so that the building could function as a mosque once again, as it has been standing derelict ever since an earthquake in 1894. It had been previously used as a mosque during the Ottoman period and was locally known as Imrahor Ilyas Bey Camii, or simply as Imrahor Camii, named after the 15th century sultan. This wasn’t shocking news as the re-purposing of historic cultural monuments for religious use was nothing new, but I feared that construction had already started and I felt the urgent need to see the building in person before its imminent makeover. I didn’t have a smart phone, but I studied a Google map the night before my walk. And luckily, from atop one of the towers at Yedikule, I spotted the minaret of Imrahor Camii in the distance above the rooftops and headed in that general direction.

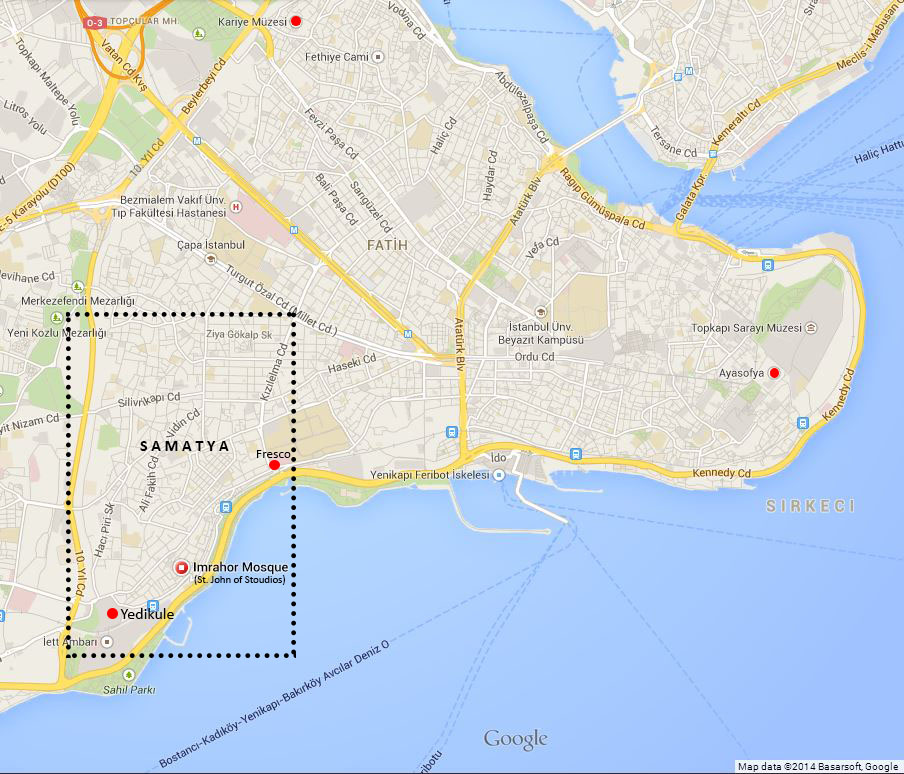

Map of the Fatih district of Istanbul. The Samatya neighborhood is outlined. Courtesy of Google Maps, with additions by author.

The opposite view towards Yedikule (east tower is circled) from the minaret of Imrahor Camii, looking west over the Samatya neighborhood, February 1937, photo by Nicholas Artamonoff

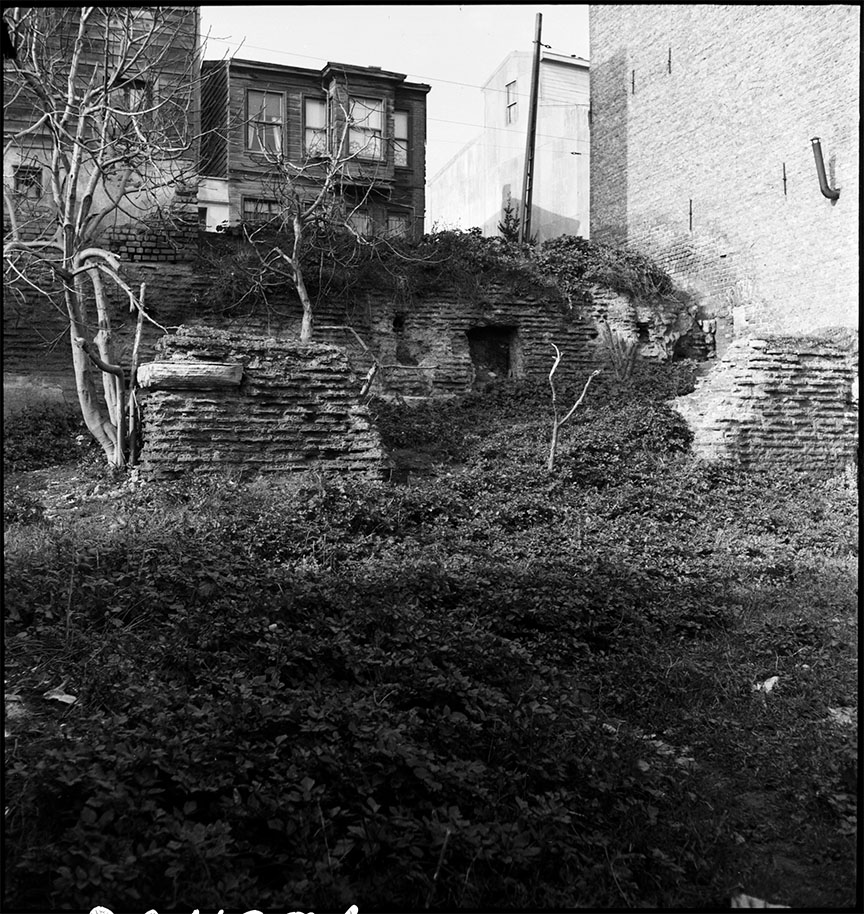

Unidentified remains of the church of an unidentified monastery located near the tram line in Samatya, January 1944, photo by Nicholas Artamonoff (ICFA.NA.0302). Not to be confused with the site of the Samatya fresco.

Site of the Samatya fresco. A man, possibly Lawrence Majewski, inspects the fresco in a small apse, c. 1957, photo by Carroll Wales

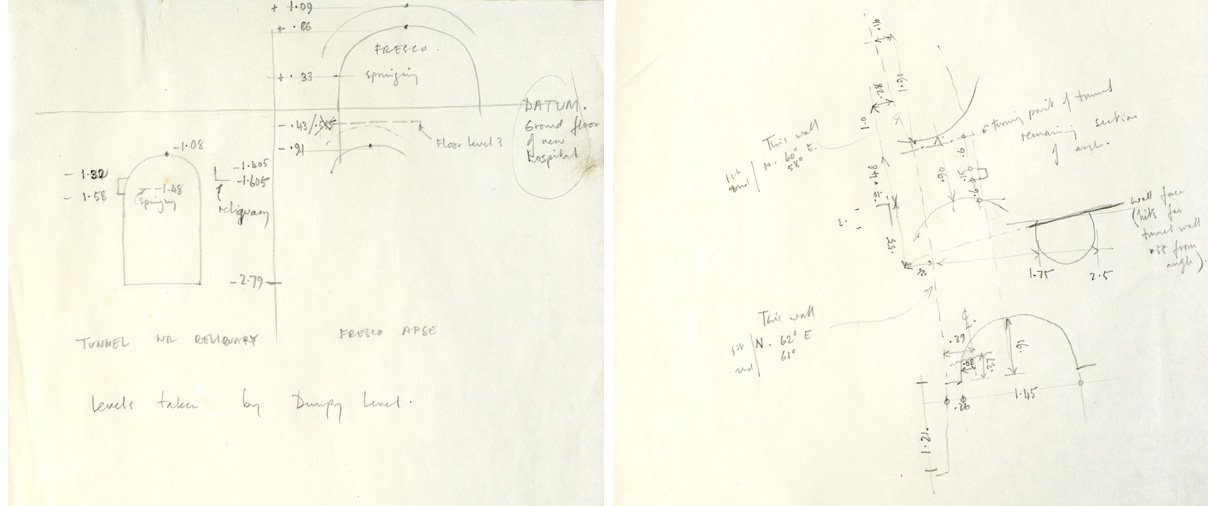

Quick survey notes and measurements of the Samatya fresco site labeled as “niche with fresco near Yidi Kuli”, from the Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks Fieldwork Records and Papers

Coincidentally, I ended up walking down the street named after Imrahor Ilyasbey and stopped in a market to buy snacks and ask for directions. I knew not to ask “where is St. John Stoudios?” I had already learned from my earlier mistake of asking someone “where is Sts Sergius and Bacchus?” when I should have asked “where is Küçük Ayasofya?” (meaning Little Hagia Sophia), as locals would know buildings by their Turkish names, not their former Greek ones. St. John Stoudios is now known as Imrahor Camii, and luckily my destination was right around the corner. I immediately thought about all of the photographs I had seen of the former monastery that ICFA has acquired over the years and hoped I could get just one glimpse of the inside. But to no avail. I was saddened as I approached the west door only to be welcomed by a sign reading “closed to visitors.” I circled around the building trying to find a better view, but only encountered more walls and barriers. While it was sad to see the old neglected structure standing in ruins, the simple fact that it was still standing and construction had not yet begun, filled me with joy.

The Samatya fresco of the Virgin and Child in a small apse, before removal, 1957, photo by Carroll Wales

Constantine Tsaousis and Carroll Wales cutting the Japanese mulberry paper and layers of muslin into twelve sections for easier removal of the fresco, 1957

The assembled fresco attached to a new armature, 1958

There it was, the centuries-old St. John Stoudios. Though it may not be as prominent in the landscape as it once was, nor garnered as much attention as monuments like Hagia Sophia, the remaining structure stands as existing proof of the most powerful and influential monastery in the former Byzantine empire. Much of its contemporaneous surroundings in the Samatya neighborhood, including other monastic churches, have been destroyed over time, but luckily some are preserved in various photographic records in ICFA’s collections. I have highlighted a few photographs from ICFA’s Nicholas V. Artamonoff Collection in this post to better illustrate the Samatya neighborhood.

If you continue with me on my walk a little farther east from St. John Stoudios, but still in Samatya, we get back to Carroll Wales and the rest of the story, which takes place almost 60 years ago. Of the various Byzantine Institute projects I mentioned before, one project has been vaguely described as the removal, transfer, and conservation of a Byzantine fresco simply called the “Etyemez fresco” in one of ICFA’s documents describing the chronology of Byzantine Institute projects. This particular project always puzzled me as I had not come across photographs in ICFA associated with the name Etyemez. Over time, I’d come across multiple images identified as “fresco at Sumatya,” or “Samatya site,” which were equally vague without further description. We also have some survey sketches ambiguously labeled “niche with fresco near Yidi Kuli.” Misspellings and different place names only help if you know that the place being described is all simultaneously referred to as the Etyemez region, Samatya neighborhood, the Koca Mustafa Paşa area, and happens to be near Yedikule. While reading a Byzantine Institute report in the Dumbarton Oaks Papers from 1960, I came across a contribution (with illustrations) by conservator Lawrence J. Majewski entitled “The Conservation of a Byzantine Fresco Discovered at Etyemez, Istanbul.” The photographs of the fresco published in the report match those that are labeled “Samatya fresco” in our photograph collection, and Wales’s additional photographic documentation sheds more light on the technical aspects of the restoration work.

Majewski wrote (published in Dumbarton Oaks Papers No. 14, 1960):

In October 1957 a Byzantine fresco of a Virgin and Child of the Blachernitissa type was discovered in the Etyemez quarter of Istanbul in the course of excavations for the addition of a wing to the İşçi Sigortaları [Kurumu İstanbul] Hastanesi (Labor Insurance Hospital) which is situated at the northeast corner of Samatya Caddesi and Etyemez Tekke Sokaği about one and three quarters kilometers from the Golden Gate (Yedikule). The director of the Ayasofya Museum, Bay Feridun Dirimtekin, was notified of the find and he in turn requested the staff of the Byzantine Institute to remove the painting and install it in the Ayasofya Museum since the structure in which it was found was to be razed.

Under the existing conditions and time constraints, it was not possible to conduct a proper survey of the site, but quick measurements and sketches were made. The demolition for the hospital expansion was halted; a period of only three days was granted for removing the fresco.

Wales and Tsaousis cleaned and removed the fresco in twelve sections under the supervision of Majewski, who assisted with the physical transfer and reconstruction of the fresco. Majewski recognized different periods of painting in three layers of fresco, all dating from the eleventh to fourteenth centuries.

In Wales’s color slides, I came across wonderful images of Wales and Tsaousis working side by side as they would continue to do for 35 years, both for the Byzantine Institute and independently when they ran the restoration business Oliver Brothers in Boston until 1987. Here, they have applied Japanese mulberry paper to the fresco surface with polyvinyl acetate as an adhesive, plus three layers of muslin for plaster application, which served as a hard support while cutting the fresco into pieces and pulling it away from the masonry.

The twelve pieces of fresco were then restored to their original shape on a semidome support (pictured above). The facing initially applied to the fresco surface was removed with solvents. Some of the second period layer of paint was also removed to reveal more of the Virgin’s head and hands. The reassembled fresco was transferred once again and mounted onto a new armature, for display in the west gallery of the Ayasofya Museum.

Today, the site of the Samatya fresco is a huge bustling hospital complex. As I walked down Samatya Caddesi towards the edge of the neighborhood, I was transported back to the modern day living and breathing Istanbul. Never would I have known that there once stood a small Byzantine church on the northeast corner of the intersection at Samatya Caddesi and Etyemez Tekkesi Sokaği. Here is a photograph taken in 1959 after the demolition of the church site:

Walking through Samatya, one sees the layers of remains of the past, some preserved, some crumbling, some integrated into the urban landscape and reused. But the things that have been destroyed remain unseen. Thanks to the work and thorough documentation done by the Byzantine Institute, and the longtime partnership of conservators like Wales and Tsaousis, even smaller and less monumental examples of Byzantine art survive for a little while longer. Reminiscing about that summer day has provided me with a whole other dimension to understanding not only the importance of historic preservation in the face of urban and modern development, but also the processes and effects of conservation, and the teamwork and partnerships that are forged by it. This relatively small project in Samatya serves as a reminder of how much has been saved despite how much has been lost against the sands of time, but also points to the reality of how much has been lost or destroyed, and not documented. I am more amazed now that a place like St. John Stoudios is still standing, yet I wonder why it remained in such ruinous conditions while it was under the jurisdiction of the Ayasofya Museum, until its recent transfer to the Ministry of Religious Affairs. Although the remaining structure, and whatever additional construction takes place, will be used as a mosque, perhaps St. John Stodios will gain more notice in the future as a living and breathing center for the surrounding community.

View of new armature housed in the Ayasofya Museum, before final plastering and painting, 1958

The fully installed fresco, after being filled in with plaster and painting, at the Ayasofya Museum, 1958

Back to our Fine Art Restoration, Repair & Conservation Services page | or directions to our Studio LINK

Contact Oliver Brothers or call us to schedule an appointment at 617-536-2323

"*" indicates required fields