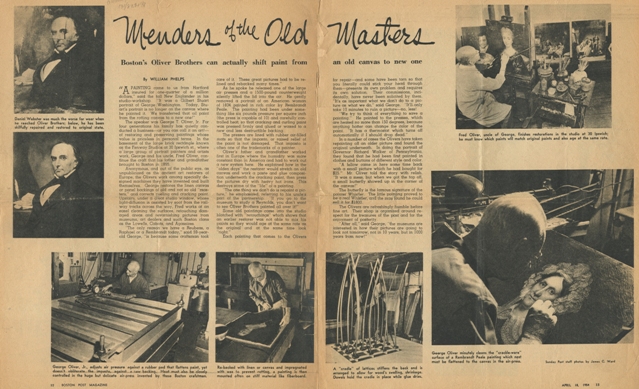

MENDERS OF THE OLD MASTERS:

Boston’s Oliver Brothers can actually shift paint from an old canvas to new one.

By William Phelps

Boston Post Magazine, April 18, 1954

“A painting came to us from Hartford insured for one-quarter of a million dollars, “ said the tall New Englander in his studio-workshop. “It was a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington. Today, Stuart’s portrait is no longer on the canvas where he painted it. We transferred that oil paint from the rotting canvas to a new one!”

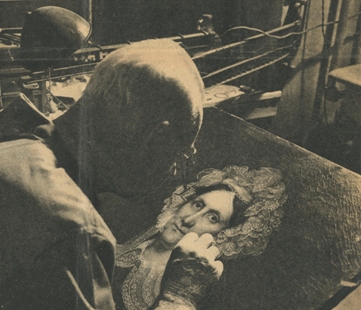

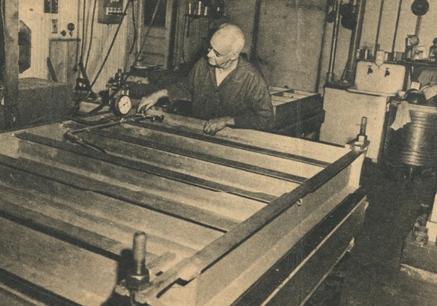

George Oliver minutely cleans the “crackle-ware” surface of a Rembrandt Peale painting which next must be flattened to the canvas in the air press.

Fred Oliver, uncle of George, finishes restorations in the studio at 30 Ipswich; he must know which paints will match the original paints and also age at the same rate.

The speaker was George T. Oliver, Jr. For four generations his family has quietly conducted a business—or you can call it an art!—of restoring and preserving paintings whose value s priceless in personal terms. In the basement of the large brick rectangle known as the Fenway Studios at 30 Ipswich st., where a large group of portrait painters and artists work, George and his uncle, Fred Oliver, continue the craft that his father and grandfather brought to Boston in 1895.

Anonymous, and out of the public eye, as unpublicized as the ancient art restorers of Europe, the Olivers work among specially designed machines they have invented and built themselves.

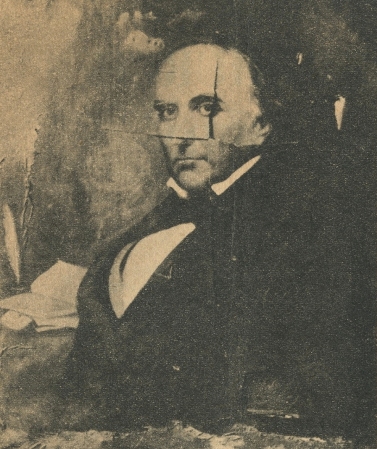

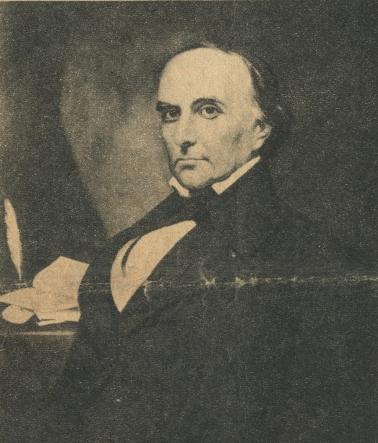

Daniel Webster was much the worse for wear when he reached Oliver Brothers; below, he has been skillfully repaired and restored to original state.

George Oliver, Jr., adjusts air pressure against a rubber pad that flattens paint, yet doesn’t obliterate the impasto, against a new backing. Heat must also be closely controlled in the huge but delicate air-press invented by these Boston craftsmen.

Re-backed with linen or canvas and impregnated with wax to prevent rotting, a painting is then mounted often on stiff material like fiberboard.

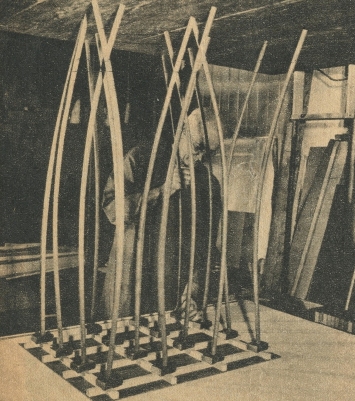

A “cradle” of lattices stiffens the back and is arranged to allow for wood’s swelling, shrinkage. Dowels hold the cradle in place while glue dries.

George restores the linen canvas of panel backings of old and not so old “masters” and corrects peeling and cracking paint. Upstairs, under a great studio window, whose light-diffusion is assisted by soot from the railway tracks across the way, Fred works at an easel cleaning the surfaces, retouching damaged areas and revarnishing pictures from museums, art dealers and such Boston clans as the Lowells, Cabots, and Agassizes.

“The only reason we have a Reubens, a Raphael or a Rembrandt today,” said 59-year-old George, “is because some craftsman took care of it. These great pictures had to be relined and rebacked many times.”

As he spoke he released one of the large air presses and a 1500-pound counterweight silently lifted the lid into the air. He gently removed a portrait of an American woman of 1834 painted in rich color by Rembrandt Peale. The painting had been under something like six pounds pressure per square inch (the press is capable of 10) and carefully controlled heat, so that cracking and curling paint was pressed firmly and blued or waxed to a new and less destructible backing.

The presses are lined with rubber air-filled mats so that the impasto, or raised relief of the paint is not damaged. That impasto is often one of the trademarks of a painter.

Oliver’s father and grandfather worked first in Europe where the humidity was more constant than in America and had to work out a new system here. He explained how in the “olden days” the restorer would stretch an old canvas and work a paste and glue composition underneath the cracking paint, then press the pictures dry with heavy hot irons. This destroys some of the “life” of a painting.

“The one thing we don’t do is repaint a picture,” he emphasized, referring to his uncle’s part of the partnership. “If you go to the museum to study a Reynolds, you don’t want to see Oliver Brothers painted all over it!”

Some old paintings come into the studio blotched with “retouchings” which shows that an earlier restorer was not able to mix his paint so thy would age at the same rate as the original and at the same time look “right.”

Each painting that comes to the Olivers for repair—and some have been torn so that you literally could stick your head through them—presents its own problem and requires its own solution. Their commissions, incidentally, have never been solicited by them. “It’s as important what we don’t do to a picture as what we do,” said George. “It’ll only take 10 minutes to ruin a picture—no, less!

“We try to think of everything to save a painting.” He pointed to the presses, which are heated no more than 150 degrees, because anything hotter can change the color of the paint. “It has a thermostat which turns off automatically if I should drop dead.”

In a number of cases the Olivers have taken repainting off an older picture and found the original underneath. In doing the portrait of Governor Richard Walker of Pennsylvania, they found that he had been first painted in clothes and buttons of different style and color.

“A fellow came in here some time back with a small picture which he had bought for $25.” Mr. Oliver told the story with relish. “It was a mess, but when we got the top off, a small butterfly showed up in the corner of the canvas!

The butterfly is the famous signature of the painter Whistler. The little painting proved to be a real Whistler, and the man found that he could sell it for $1800.

The Olivers are refreshingly humble before fine art. Their shop is organized around respect for the treasures of the past and for the employment of posterity.

“After all,” said George, “the museums are interested in how their pictures are going to look not tomorrow, not in 10 years, but in 1000 years from now!”

*Sunday Post Staff photos by James C. Ward